How galaxies form and evolve across cosmic time is one of the major research questions in modern astronomy and cosmology (Australian Decadal Plan for 2016-2025). Key aspects of the origin and evolution of galaxies are poorly understood, but studying our own Galaxy offers one of our best opportunities at understanding spiral galaxies more generally; a near-field approach to cosmology. However, understanding the formation history of the Galaxy is a challenging puzzle.

The present state of the Galaxy is a result of various complex physical processes occurring simultaneously over its lifetime. The situation is further complicated by the fact that we only have access to the current snapshot of the Galaxy. Fortunately, encoded in the light of the stars are clues that nature has left for us to solve this puzzle. The chemical compositions of stars are shaped by events from the Big Bang through nuclear burning in successive generations of stars until the present day. Because the elements have distinct nucleosynthetic origins in different types of stars with varying lifetimes, the combination of many stellar elemental abundances allows astronomers to tag individual stars to their place of birth and the physical conditions prevailing at that time. The age of a star can be estimated using information in stellar spectra. Furthermore, kinematic data carries information about past episodes of accretion and heating as well as resonances and other drivers of migration in the disk. It is all these stellar properties that we are measuring with GALAH.

The April 2018 release of Gaia DR2 has been a game changer in the field of Galactic science. In particular, the parallax measurements from Gaia allow the identification of main sequence turnoff and sub-giant stars, and determination of their ages to 10% precision. Obtaining ages enables a wide range of projects that shed light on several outstanding questions in stellar and Galactic science. Having precise age estimates for a large number of stars adds new dimensionality to previous work, and opens up a new realm of possibilities that we aim to explore in GALAH.

The GALAH Survey Science goals:

Changes with time

After their birth-clusters or birth-galaxies disperse, stars may change their dynamical behavior thanks to mechanisms like heating and radial migration. However, the chemical composition of these stars, which reflect the conditions of their birth locations, remain largely unchanged. When fossil relic stars from these dispersed clusters are discovered, we are working with Gaia, K2 to estimate accurate ages for the GALAH sample. This age information will let us develop a picture of the assembly of the Milky Way. We can then place these reconstructed stellar clusters into an evolutionary sequence, i.e. a family tree, based on their chemical signatures. This allows us to estimate a timeline of the Galaxy’s chemical and dynamical evolution, including its accretion history.

We can investigate if the star formation history of the Milky Way continuous, or is it split into distinct episodes? Some studies suggest that there is a quenching of star formation at around 8–10 Gyr, and this is linked to the origin of the thick disc, while others suggest a continuous star formation history. The precise ages from GALAH for a large number of stars can directly answer this question. A number of recent studies suggest that using chemical evolution models one can fit for trends of some specific elemental abundances with age and recover the star formation history.

Accretion History

Interacting galaxy pair Arp 87. Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA).

Interacting galaxy pair Arp 87. Credit: NASA, ESA, and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA).

GALAH focuses its observations on the Milky Way disk and bulge, which contain almost all of the stellar mass of the Galaxy. These components, in addition to evolving dynamically, may also be influenced by the infall of small evolved satellite systems. Gaia has revealed the velocity space in the solar neighborhood to be rich with substructure, showing numerous clumps belonging to various moving groups. Some of these clumps are likely the debris of old disrupted star clusters in the disk, which are now dispersed into extended regions of the Galaxy. Others may be remnants of satellites cannibalized by the Milky Way. It has already been shown with GALAH data, these moving groups have unique chemical signatures. GALAH is giving us a large enough sample size to resolve these substructures by age, which can reveal the origin of these structures, e.g., orbital resonances due to bar or spiral arms, disruption of large clusters or star forming complexes, or outside perturbations

Dynamics

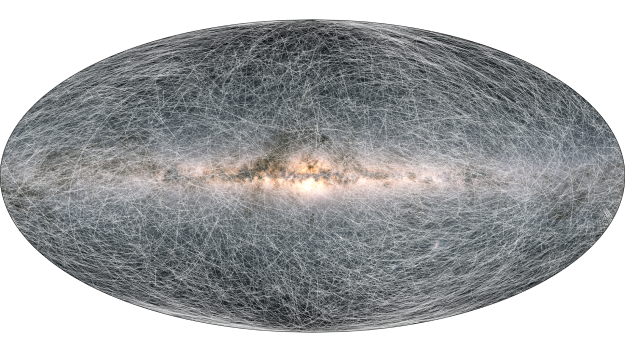

The trails on this image show how 40 000 stars, all located within 100 parsecs of the Solar System, will move across the sky in the next 400 thousand years. Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO.

The trails on this image show how 40 000 stars, all located within 100 parsecs of the Solar System, will move across the sky in the next 400 thousand years. Credit: ESA/Gaia/DPAC, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO.

The GALAH sample can be used for examining the dominant dynamical processes that occur during Galaxy development. Without radial mixing, the dispersed debris from open clusters detected by GALAH would be on near-circular orbits and confined to a fairly narrow annulus around the Galaxy, reflecting their early dynamical properties. Using GALAH, we can examine the radial extent of the chemically-tagged debris of disrupted clusters; we will then have a direct measurement of how important radial mixing, and other dynamical processes, has been to Milky Way evolution.

Different radial mixing processes bring metal-rich/-poor stars from the inner/outer regions of the disc to the solar neighbourhood. Hence, the metallicity distribution of stars in the solar neighbourhood can be used to place constraints on the amount of radial mixing. Elements other than iron are also useful for this purpose. However, the relative efficiency and time scales of different mixing processes (i.e., blurring vs. churning) are unknown. If we have age information for a large number of stars, we can study radial mixing as a function of time and provide tighter constraints to models of Galaxy evolution.

Nucleosynthetic Processes

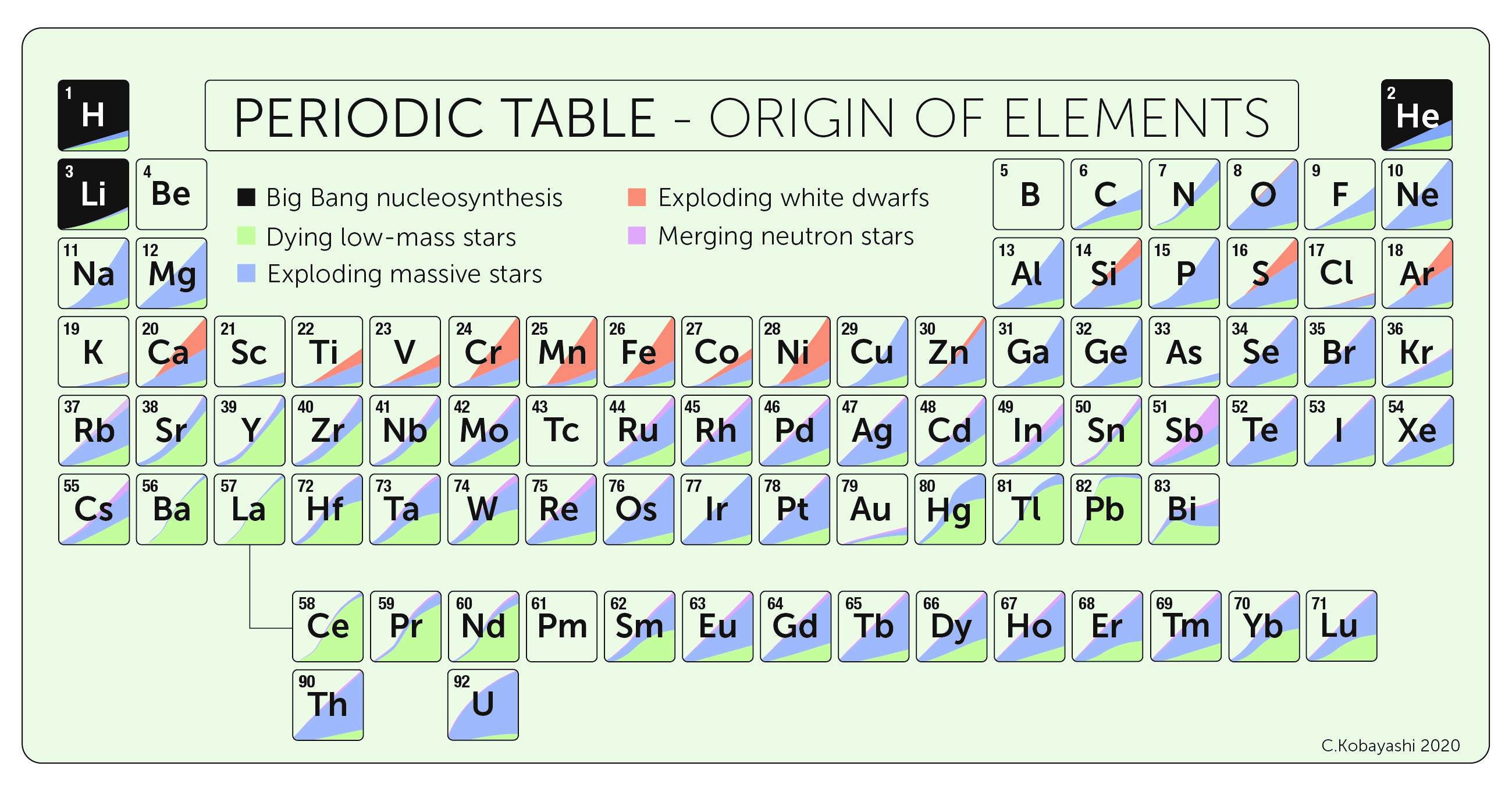

The Periodic Table, showing naturally occurring elements up to uranium. Shading indicates stellar origin. (Content: Chiaki Kobayashi *et al.*; Artwork: Sahm Keily)

The Periodic Table, showing naturally occurring elements up to uranium. Shading indicates stellar origin. (Content: Chiaki Kobayashi *et al.*; Artwork: Sahm Keily)

The large, homogeneously observed and analyzed GALAH stellar sample can be used to help to separate the different nucleosynthetic processes that lie behind the chemical evolution of the Galaxy. For instance, in the solar neighbourhood, there is a clear dichotomy between two sequences in the [α/Fe]–[Fe/H] abundance space: a high-[α/Fe] sequence and a low-[α/Fe] sequence, traditionally referred to as the thick and thin discs. The origin of these two sequences has proven difficult to explain, and has lead to increasingly complicated models of chemical evolution. It is also possible that these two sequences are (partly) coeval, reflecting instead the chemical evolution of different areas of the Galaxy. Existing observations are inadequate to disentangle the origin of these two populations. A region of particular interest is right on the boundary between the two sequences and where the two sequences begin to merge. With our current data, there are only a handful of stars between 8 and 9 Gyrs, which is not enough to determine the origin of the different populations.

Chemical Tagging

Elemental abundances are birth tags that cannot be erased unlike kinematic or positional information. This leads to the elegant notion of using elemental abundances patterns to identify stars sharing a common origin. Recent studies on the practicality of chemical tagging have been encouraging. Previous research has looked at the theoretical capabilities of chemical tagging in a large dataset to investigate the connections between data quality, survey size, and level of recovered detail on the star formation history. In the thick disk specifically, it has been calculated that for a mock GALAH survey with one million stars, we should detect ten stars (a reasonable minimum number for confident chemical tagging) for all clusters down to an initial cluster mass of about 100 solar masses. The initial cluster mass function has a negative slope, meaning that there are more low-mass star-forming groups than high-mass ones. Increasing the size of the GALAH sample reduces the minimum cluster mass that can be resolved by GALAH, meaning that we can track the star formation history of the disk more completely. These predictions underline that our sample size and data quality goals have real consequences for the scientific capabilities of our project.